You are here

Home ›Education Strikes from West Virginia and Kenya to the UK

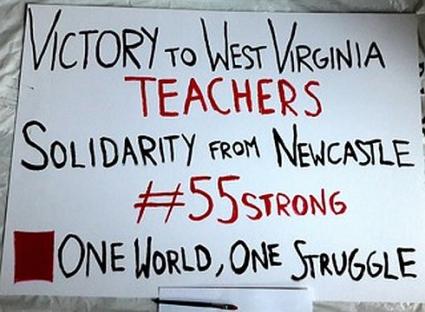

On Sunday March 25 the CWO held a meeting in Newcastle focussing on the recent educational strikes across the world. It was attended by students, academics and other university workers (some in the CWO, some not) who had participated in the recent pickets of Newcastle, York and Durham universities. A CWO comrade gave the following introduction.

Introduction

I will start off with a short introduction to the recent wave of strike action that we have seen internationally in the education sector in February and March. I will talk a bit about Kenya, but primarily focus on West Virginia and the UK on which we have more information. I’ll finish off with some observations on the class composition of the strikes, solidarity (or lack of it) with other sections of the working class, as well as the role of unions. And then hopefully we can have a bit of a discussion.

Kenya

The nationwide lecturer’s strike in Kenya came in the aftermath of previous strike action in December of 2017. In December the two unions involved in the dispute: the Universities’ Academic Staff Union (UASU) – a kind of equivalent of the UCU in the UK – and the Kenya Medical Practitioners, Pharmacists and Dentists Union (KMPDU) – similar to the BMA, ended the strike after the government promised to negotiate a new collective bargaining agreement. That promise however was non-binding and realising they may be getting shafted, the workers resumed the strike on the 1st of March. The demands of the strike remained the same – a pay raise, but also access to services available to other public servants (such as car loans) as well as higher quality medical insurance. In addition there is the issue of pension benefits owed to retired staff which allegedly amount to around $34 million.

27,000 university staff together with 9,000 lecturers are said to have joined the strike which paralysed nearly all of the 31 public universities in the country. Among them are medical student interns and professors. In response, the universities have petitioned the government to stop the strike. On 16th of March the Kenyan Labour Court declared the strike illegal. Rather than give in however and despite threats from VCs that striking staff will be fired, the workers continue the strike which has now entered its fourth week.

West Virginia

Turning our attention to the United States, on February 22nd workers in West Virginia walked out over a proposed pay raise of 2%, followed by 1% increases in 2020 and 2021, which they deemed not enough. Over 20,000 teachers, bus drivers, office workers, and cooks, took to the picket lines shutting down schools across all 55 counties. All this in West Virginia, a state which in 2016 overwhelmingly voted for Donald Trump and has been deemed by commentators part of the so called ‘Trump country’. What initially started as a strike called by three trade unions, the American Federation of Teachers, the National Education Association, and the School Service Personnel Association, grew into a real movement when the unions tried to sell out the strike on February 27th. Governor Jim Justice reached a compromise with the unions which promised a 5% pay increase to teachers. Not only was this a non-binding agreement, again like the one in Kenya, lawmakers also agreed to knock it down to 4% and it left out other sectors of the workforce altogether.

Despite the proposed deal, the strike continued. The defiance of the workers inspired others – on the 4th of March, 1,400 West Virginia Frontier Communications workers went on strike. Teachers in other states, such as Oklahoma, declared they might follow suit. Some students also rallied behind their teachers, adopting the colour purple in solidarity (a combination of red and blue, the two colours of the teachers' union). In the face of a growing opposition, a new deal was agreed by the unions and the state this time promising a 5% raise not only for teachers, but for all public employees. On the 7th of March workers returned to work. Touted as a victory by the media and the unions, the new deal however leaves many questions unanswered – how will the pay raise be funded? And what about the other grievances of the striking workers such as a properly funded Medicaid? [For more on this see leftcom.org]

UK

The situation in the UK is likewise a result of a botched union deal that dates back to 2015. Back then UUK, the employer’s association, sought to impose dramatic cuts to the USS pension scheme on the basis of a supposed massive deficit. Back then the same debates were held over the profitability of the pension scheme as today, with lecturers arguing the deficit is a trumped-up excuse to attack staff pensions. So why is the same dispute being revived again? Because in 2015 UCU agreed to a revised offer, which included only minor tweaks, and backed down from a marking boycott. Now in 2018, UUK is continuing its assault on the pension scheme in its attempt to change it from a ‘defined benefits scheme’ (where retirement income relates to earnings) to a ‘defined contributions scheme’ (where retirement income is determined by how their pension funds have performed on the stock market). This reform, apart from setting up the ground for further privatisation of the universities, will also cut USS pensions by up to 40%.

In response UCU has declared 14 strike dates, which began on the 22nd of February, same day as the West Virginia strike. Up to 40,000 staff are taking part in the strike across 61 universities. And it is in the UK where student staff solidarity has been the strongest. In scenes not seen on campuses since at least 2014, 20 or so universities have been occupied by students. At many universities students have joined the picket lines and tried to make them more effective through direct action, often coordinated by small groups of students involved in pre-existing networks of the 2010 student movement. We have seen small examples of this at Newcastle University too.

On the 12th of March however, as more talks were taking place between UCU and UUK, a new deal was agreed. Essentially it was a three-year transitional period to revalue the pension scheme – the results of which are predictable. Rather than address the issue it would have just delayed the inevitable. The reaction from striking staff was immediate – outrage on social media followed, while general meetings at over 40 universities voted, often unanimously, to reject the deal that same day. A protest was organised outside the headquarters of UCU in London, where Sally Hunt, the general secretary of the union, tried to calm down the rank and file to little effect. Having no other options and facing an internal collapse of the union, UCU rejected the deal the next day. Like in West Virginia or Durham in 2016, the union now had to trail behind its own members.

After 4 weeks of strike action, the Easter break has now disrupted the momentum. What happens next is still up in the air – UCU has declared 14 more days of strike action which would target the exam period between April and June. But another shady deal could be tabled in the meantime.

Conclusion

What is common among all these strikes is of course the fact they all take place within the education sector. And that, every chance they get the unions have tried to nip the struggle in the bud by coming up with shitty or non-binding deals, only to have the rank and file reject them. These are all well educated but increasingly precarious workers we are talking about. At least in West Virginia, they are also largely women (here we could talk about the similarities with the Durham Teaching Assistants). We advertised this meeting with a quote from the Communist Manifesto, and it’s worth reading it out again:

The bourgeoisie has stripped of its halo every occupation hitherto honoured and looked up to with reverent awe. It has converted the physician, the lawyer, the priest, the poet, the man of science, into its paid wage labourers.

The proletarianisation of the professions is taking place before our eyes, and it is in the course of class struggle, that these education workers are gaining a new sense of class consciousness. Our aim should now be to extend this fight to all corners of the working class, as isolation is the grave-digger of every struggle and every movement. They cannot remain just within the education sector – they have to spread across the workforce. We have seen just the beginning of this, as 3 days ago at the University of London academic staff have voted to strike simultaneously with outsourced cleaners, security, and porters on the 25th and 26th of April. This is still taking place within the university environment, but it is a beginning. In the long run we have to overcome the boundaries enforced on us by sectionalism and legalism. We have to overcome divisions of nationality, race, gender, ability, profession and union affiliation. So maybe this is something we can discuss, what can we do as class conscious minorities? How do we move our struggles forward so that we not only win but in the process build the foundations for a new world without exploitation? What other forms of organisation exist outside of the compromised unions? We should also discuss the wider picture, of how in the era of global finance capitalism, our futures are increasingly uncertain, where the state of our pensions, benefits, access to healthcare, and even a decent life after retirement is more and more unclear.

Discussion

The questions posed in this introduction stimulated a wide-ranging discussion to which nearly everyone in the meeting made a contribution, raising a range of issues. The first was the question of solidarity. A strike over a pension scheme under the union slogan of “Your Pension Axed” doesn’t sound like a promising basis for solidarity. In fact it was the student support across the country that went beyond the slogan. Most of these were initiated by students themselves through setting up of staff-student solidarity committees. One comrade who had, as a student, participated in the 2010-11 university lecturers’ strike contrasted the experience then with now. He had tried to get students to solidarise with lecturers then but at that time all they were concerned about was the loss they might be suffering as a result of the action. He evoked some laughter when he told of his encounter with one student who he challenged not to cross the picket line. The latter looked at the floor and said he could see no line there!

Things have obviously moved on and current student support prompted wider participation by staff in the strike. This led to a wider reflection amongst some of them about the significance of the strike. In Durham they started to discuss the “commodification” of education and what this tells us about the society we live in. This was not just theoretical reflection. In an attempt to reach out to the wider society lecturers even started giving free talks on their specialisms (which ranged from anthropology and archaeology to biosciences and physics) in “teach-outs” in a “free university” to which anyone was welcome – and this happened at a number of universities. Obviously it only involved a small minority of lecturers but it was an imaginative alternative which not only helped to take the action forward but even hinted at what education might be like in a saner society where the law of value did not rule. A Newcastle student pointed out that there was plenty of money for University expansion as it took over more and more of the city but the social consequences of this (such as the impact on housing costs for all) were never considered.

In sub-zero temperatures picketing took some commitment but this did not stop more than the legal 6 pickets assembling each day. The police presence seem to have ignored the fact that most of the student pickets were breaking the law and did not even intervene when they succeeded in actually briefly blocking one of the entrances to Newcastle University. It was left to the university security to break up the blockade, while the complaints about going beyond the legal 6 pickets were only raised by university HR and a local UCU rep who told the students to disperse as it “is my picket line”.

Such talk led on naturally to a discussion of the role of the trades unions. At best they have been irrelevant (apparently even getting strike pay is like going through the DWP interrogation of the dole offices) and at worst, the unions in all the disputes we discussed have been saboteurs. In West Virginia the unions accepted the Governor’s verbal promise of a 5% wage rise (which they had not asked for) but did not meet the more important demand for increased medicare payments. The union though accepted this and just informed the strikers by automated telephone message that the strike was over. As the introduction to the meeting said UCU are expected to do something similar in the UK. More than one person pointed to the obstruction and lack of communication of the union. The only real actions were those carried out on local initiative. The union bureaucracy have their own agenda.(1) Having had their initial attempt to sell the strike out rejected by general meetings they want their members to accept the new proposal to kick the dispute into the long grass for a year thus allowing the bosses time to regroup. We expect them to take advantage of the Easter holiday break when the solidarity of face to face meetings is temporarily broken and just have an online ballot (thus breaking the collective decision making of those involved) to end the fight.

Looking at the wider context of the strike many in the meeting expressed how participation in the struggle had given them confidence. Others pointed to the fact that after years of restructuring in which the old manufacturing sector had declined from 26.4% of the workforce in 1978 to 7.8% at the end of 2017 we were faced with a new class composition in which the former professions were now being proletarianised. This does not just mean that they were having to fight like everyone else for their wages and conditions but also to get back some control over the decisions about how to do their job well. The gig economy has produced a number of struggles over the years but between these two sections of the working class there lies the basis for a resistance to the continual decline of living and working conditions. This has not just come as a result of the fall in wages since the speculative bubble burst in 2007-8 (some 10% on average) but goes much further back to the end of the post-war boom. It came about in the 1970s when for a few years workers fought the attacks made upon them until the rise of unemployment at the end of the 1970s put them on the back foot. The state then did what many had thought unthinkable and abandoned its support for the “commanding heights” of the economy. By sacking workers in them en masse they destroyed the basis for the fight. After four or more decades of retreat (wages as a share of GDP have fallen since 1979) we now have a new working class which may not be so pliable as in the past. The key will lie in how far it is prepared to act for itself in its own interest.

Material victories were important and recent victories by the likes of the Daily Mail cleaners can only encourage wider resistance but the real gains from all these struggles is the wider experience in self-organisation and collective resistance to a system which intends to drive down the living standards of workers everywhere. The meeting was summed up by the CWO chair who thanked everyone for their contribution. She concluded that whatever the various struggles produced in terms of gains in confidence and self-organisation it was clear that unless workers organised beyond the immediate struggle and created a political body to represent their real interests then we would be forever starting from “ground zero”.

CWO

31 March 2018

Notes

(1) For our wider views on unions see leftcom.org

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

- By cheque made out to "Prometheus Publications" and sending it to the following address: CWO, BM CWO, London, WC1N 3XX

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2006: Anti-CPE Movement in France

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and Autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

Comments

And on it goes nytimes.com